By akademiotoelektronik, 21/04/2022

Outline Closer to Disposables than Notables Paul Tibbets, the Atomic Bomb and the Pilot

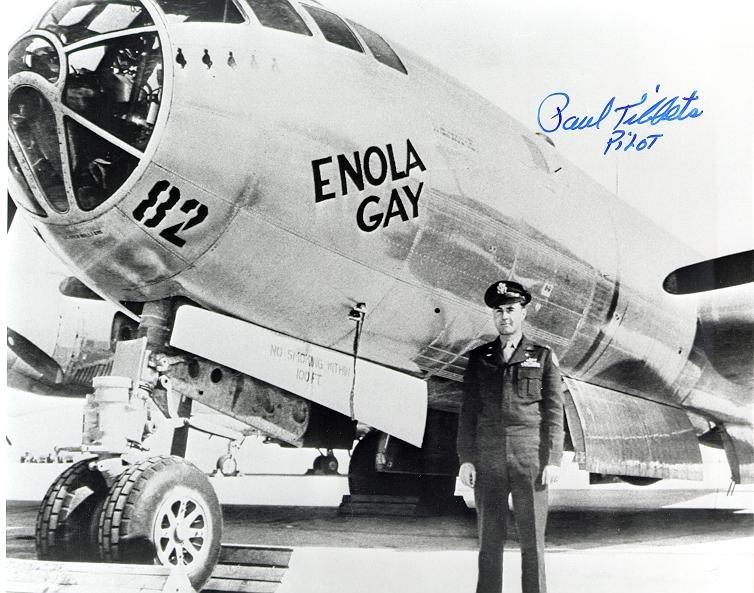

Paul Warfield Tibbets was the pilot of the Enola Gay, the plane that bombed Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, killing 140,000 civilians. Studs Terkel met him in 2002, an interview originally published by The Guardian [1]. The review More than words published a translation, which we reproduce below [2]:

Studs Terkel — Here we are both sitting at Paul Tibbets in Columbus, Ohio. This is where this 89-year-old retired general has lived for several years.

Paul Tibbets — Hey, I can't let you say such a thing. I'm only 87, not 89.

OK. I'm 90 myself, so I'm three years older than you. We have just shared an excellent meal, you, me and your companion. I noticed that while we were sitting in the restaurant people were walking by and had no idea who you were. However, you once piloted an airplane, the Enola Gay, which, on the morning of Sunday August 6, 1945, dropped a bomb on the city of Hiroshima, Japan. It was an atomic bomb, the very first of its kind. This event changed the world, and it was you who were in control of this aircraft.

Yes quite.

The name of the aircraft referred to…

To my mother. Her name was Enola Gay Haggard before she married my father. He never wanted me to become a pilot, he hated planes and motorcycles. When I told them that I was going to quit school and join the air force to fly planes, he said to me: "I financed your studies, your cars, your outings with girls but, from now on, don't count on my support. If you really want to kill yourself, go ahead, I don't care. My mother then added calmly, "Paul, if this is what you want, then this is the right choice." »

Where was this happening?

Well, it was in Miami, Florida. My dad had worked in real estate there for years, but he was retired at the time. I was going to school in Gainesville, but since the state of Florida didn't have a medical school, I had to move to Ohio.

Did you think of becoming a doctor?

Not me, but that was what my dad wanted. I was content not to contradict him. That was the path I was on, and then a year before this discussion took place, I had the opportunity to fly a plane on my own. I knew right away that was what I wanted to do.

In 1944, you became a test pilot assigned to the development of the B-29. When did you learn that you were being reassigned to a less conventional program?

One day [3], I'm doing a test flight on a B-29, and a man picks me up when I land. He tells me that he has just received a phone call from Colorado Springs, and that General Uzal Ent [4] wants to see me in his office the next morning at 9 o'clock. He adds that I must take my complete kit and that I will not return to the base. I didn't know what it was all about, but it didn't bother me. This was just a new assignment.

The next morning, I showed up perfectly on time for the appointment in Colorado Springs. A man named Lansdale greeted me and led me to General Ent's office, then closed the door behind me. The general was accompanied by a US Navy officer in full uniform – it was William Parsons who will be part of my crew on the flight to Hiroshima – and Norman Ramsey, a nuclear physics professor from the columbia university. The latter began to explain to me the existence of the Manhattan project, the objective of which was to develop an atomic bomb. He went on to tell me that they had gotten to a point where they needed to work with planes to move forward.

He gave me a detailed explanation that lasted about 45-50 minutes, then left the office. General Ent looked at me then and said: “a few days ago, General Arnold [5] offered me three names. The other two officers had the rank of colonel, while I was only lieutenant-colonel. He explained to me that when General Arnold had asked him who might be suitable for this mission, he had given him my name without the slightest hesitation. I thanked him, he then began to explain to me the task that awaited me: to form a team and train it to launch atomic weapons in Europe and the Pacific.

It is interesting to know that Europe was also a target in their eyes. This is not information known to the general public.

My mission could not be clearer: I had to simultaneously drop a bomb on Europe and another in the Pacific, it was impossible to do otherwise if we wanted to maintain the element of surprise. General Ent then told me:

He continued :

I thanked him again. He concludes by saying:

Did you know the power of an atomic bomb? Were you told about this?

No, at that time, I didn't know anything about that kind of detail. But I knew how to put together a team. General Ent had told me to go around the military bases and tell him which one I wanted to use. I had every intention of returning to Grand Island, Nebraska, as that was where my wife and two children were. But I said to myself that I would still go to Wendover [6] first and see what was going on. As soon as I arrived, I could see that it was a magnificent place. It was there that the pilots received the end of their training. The guys in front of me belonged to units that flew P-47 fighters. The officer commanding the base told me:

This is when you choose your crew members…

In fact, I had already chosen them in my head. I knew without hesitation that there would be Tom Ferebee (bomber), Theodore “Dutch” Van Kirk (navigator) and Wyatt Duzenbury (flight engineer).

Were they guys you had flown with in Europe before?

Yes.

You are now in the training phase. You are in communication with physicists like Robert Oppenheimer [7].

I think I have been to Los Alamos [8] three times and seen Dr. Oppenheimer working there each time. Looking back, thinking about it, he was a brilliant young man. He smoked like a firefighter and drank cocktails. And he hated fat people. General Leslie Groves [9] was fat, and he hated smokers and drinkers. They were a very strange old couple.

They didn't get along?

No, but they didn't show it. They were conscientious.

Does Oppenheimer tell you about the destructive power of the bomb?

No.

How did you hear about it then?

Through Dr. Ramsey. The only thing he had agreed to tell me was that the bomb was going to explode with a force equivalent to 20,000 tons of TNT. I had never seen what the explosion of 500g of TNT could produce, and did not know anyone who had ever witnessed the explosion of even 50kg of explosive. I thought it was going to be a hell of a mess.

20,000 tons – how many bombers loaded with bombs would it take to get to that amount?

Well, I believe that the two bombs we dropped [10] represented more power than any we used in the war on the European front.

So Ramsey told you what could be going on?

Even though at that time things were only at a purely theoretical stage, everything these guys told me turned out to be correct. I felt ready to go into battle, but I needed to ask Oppenheimer how to extricate myself after dropping the bomb. I had explained to him that during the bombing missions in Europe and North Africa, we continued our course on the same course after dropping the bombs, which also corresponded to the trajectory of the projectiles. I asked him if this procedure could be applied in this case. He replied no, that I would then be right above the explosion and that I would be wiped off the map. According to him, I had to maneuver in order to take a tangent to the shock wave. I tell him :

He replied that to get away from the impact zone of the bomb as quickly as possible, I had to turn quickly at 159°, whatever the heading.

How long did you have to perform this maneuver?

I had dropped enough practice bombs to know that the explosion would occur about 500 meters above the ground. So I had between 40 and 42 seconds to turn 159°. I returned as quickly as possible to Wendover and put myself at the controls of my plane. I trained myself to make this turn of course at 8,000 meters altitude, increasingly tight, until I succeeded in the maneuver in 40 seconds. The plane's tail was shaking dangerously, and I feared it would break, but I didn't give up. I had set myself a goal. I trained relentlessly until I could do it automatically consistently in 40-42 seconds. So when the big day finally arrived...

You received the mission order on August 5th.

Yes. We were in Tinian [11] when we received the confirmation. A Norwegian had been dispatched to the weather station on the island of Guam [12], and I had received a copy of his report. Based on his forecast, we had estimated that the most suitable day for sailing over Honshu [13] would be August 6th. We made the final preparations: loading the plane, distributing orders to the crew, and everything that needed to be checked before going on a mission over enemy territory.

General Groves was in touch by teleprinter with an officer in Washington, DC He remained permanently near this apparatus, and transmitted a coded message informing the officials that the planes were held ready to take off from the 6th at midnight. And that's how things turned out. We had been operational for about four hours on the afternoon of the 5th, and we received authorization from the president. We were given the time for the bomb release, but since it was Tinian's time zone, which was an hour ahead of Japan's, I asked Dutch to take care of calculating the time at which we had to take off to be on our target at nine o'clock.

Sunday morning, then.

Well, we were on the trail at 2:15 sharp. We took off, joined our escort at the meeting point and flew to the place we called the starting point, which corresponded to a geographical location that we could not miss: rivers, a bridge and a large chapel. Impossible to be wrong.

So the navigator had to know what he was doing to drop the bomb.

The aircraft was equipped with an aiming system connected to the autopilot, through which the bombardier could enter information about the point of release of the projectile. We had from the beginning imagined the possibility that the door of the hold would not open and we had planned a manual opening system in each of the planes, he was at the bomber's station and he was the one who could operate. The planes that were flying behind us and had the task of dropping measuring equipment had to be warned when we were going to drop the bomb. The orders we had received were not to break the radio silence but, good God, there was no other way. So we agreed that I would recite a countdown to the last minute. This would give them time to jettison their gear, and their position would make it clear to them the nature of the task they had to perform. Everything went exactly as planned. It was perfect.

Once the planes were in formation, I slipped out of the cockpit and joined the crew. I asked them if they had any idea of the nature of our mission. They replied that it was a bombardment. I nodded, but I told them that it was a somewhat special mission. Bob Caron, my tail gunner, was a quick thinker, and he asked me:

What I confirmed to him. I returned to the front and informed the rest of the crew as well. “Okay, we're going to drop an atomic bomb. They listened to me, but didn't seem more surprised than that. These guys weren't stupid. We were handling things with one of the most peculiar shapes we've ever seen.

So we go down. I finish reciting the countdown, and barely have I pronounced the "one" when the plane, relieved of 4,500 kg, makes a sudden swerve. I begin this famous course change, as tight as possible in order to maintain my altitude and my speed. When I right the plane, I discover that the sky has completely taken on blue and pink hues. I had never seen such pretty colors in my life. It was wonderful.

I often tell people that it's like I've tasted the explosion, and they ask me what I mean by that. When I was a kid, when you had a cavity, the dentist filled the hole with a kind of mixture that he pushed in with a hammer. I had discovered that if I ate a spoonful of ice cream and touched one of those damaged teeth, I could feel that electric thrill as well as the taste of the filling. And I knew right away what it was.

We all take the way to the base. We had been ordered not to use the radios, and just turn around and set sail as quickly as possible. I decide to go back via the Sea of Japan because I know they won't be able to find us there. The return flight made, we are at the base.

Tom Ferebee is to file a report on the bomb drop, and Dutch, our navigator, a detailed account of the theft. Tom asks:

Dutch replies:

Ferebee concludes:

Did you hear the explosion?

Oh yes. The shock wave followed us after our course change. The tail gunner alerted us that we were about to be overtaken, and the next moment the impact was shaking our ass. I had accelerometers installed in each of the devices to record the magnitude of the explosion. The shock had a power of 2.5 G. The next day, when the scientists updated us on what they had learned from the drop, they explained to us that, at the time of the explosion, we were already at almost twenty kilometers from the point of impact.

Have you seen the mushroom cloud?

There are different types of mushroom cloud, depending on the bombs used. In Hiroshima, there was no fungus. It was just a vertical cloud. It was very dark, with light, colors, white and gray inside. The top looked like a bent Christmas tree.

Did you have any idea what was going on down there?

It was hell ! I think one of the historians of the project summed it up perfectly when he said that in a microsecond the city of Hiroshima was wiped off the map.

Back home, you meet President Truman.

It was in 1948. I return to the Pentagon and find myself in the office of the chief of staff of the air force, Carl Spaatz. Also present are General Doolittle and a colonel named Dave Shillen. Spaatz tells us:

Along the way, Doolittle and Spaatz were talking among themselves. For my part, I did not have much to say. As we got out of our car, we were quickly escorted to the Oval Office. A black man who worked for Truman told us how to introduce ourselves. General Spaatz stood on the right in front of the desk, then Doolittle, and finally Shillen. From a military point of view, this order respected the hierarchy: Spaatz was the superior officer, and Dootlittle was to be placed on his left.

The man then placed me on the chair that was next to the president's desk. We were offered a cup of coffee which we had almost finished when Truman entered the room. Everyone stood up. He asked us to sit down, a wide smile on his face, and said:

Spaatz thanked him and said it was a great honor for him to take on this task. Then the President addressed Doolittle and complimented him on his successful raid on Japan. It was then the turn of Dave Shillen to receive his congratulations, for having been one of the first to grasp the importance of in-flight refueling.

Then the president stared at me without saying a word for about ten seconds. When he spoke again, it was to ask me if I had any idea what I was there for. I answered him:

He knocked his hand on his desk and said:

Have you ever received criticism?

No, that never happened.

Have you ever regretted dropping that bombshell?

Regret? No. Listen, Studs. To begin with, I entered the Air Force to defend the United States as best I could. It's what I believe in and what I trained for. Then I was a very experienced pilot… Some of the missions I had done didn't really require personal involvement, but when it comes to setting up the dropping of an atomic bomb, it requires to have thought about it and to be in agreement with what that implies.

During the flight to our objective, I reflected on the mistakes I might have made. Maybe I was too sure of myself. I was 29 years old, and I was full of confidence. I thought there was nothing I couldn't do. And of course that applied to airplanes as well as to men. So I didn't have the slightest qualms about this mission. I knew we had made the right choice. When I knew what we were going to do, I thought to myself that we were going to kill a lot of people, yes, but that, thank God, we were also going to save a lot of people, and that the invasion would no longer be necessary.

Why did they drop a second bomb on Nagasaki?

What nobody knew except me was that there was a third bomb. In fact, the Japanese did not react for two or three days when the first bomb was dropped, and the same with the second. I then received a phone call from General Curtis LeMay [14], and he asked me if I still had one of these little toys on hand. I answer yes. He asks me where he is. “In Utah,” I tell him. “Go get it for me,” he orders me. You and your crew are going to dump him on me. I nod and give instructions for the bomb to be loaded onto a plane, so we can pick it up and bring it back to Tinian. But the war ended in the meantime.

What were General LeMay's plans with this third bomb?

Nobody knows.

An important question: since September 11, how do you see the situation? People talk about nuclear power, the hydrogen bomb...

To tell the truth, I don't know any more about these terrorists than you do. I know nothing. When they bombed the World Trade Center, I couldn't believe it. During our history, we have fought many enemies. But we knew who they were and where they were. With these people, we know nothing of all that. That's what worries me. Because they're going to strike again, I'm willing to bet it, and it's going to be a great disaster. They're going to do this according to their own rules of the game. We have to be able to eliminate these bastards. To drag them before a court is bullshit, I don't believe it for a second.

What about the nuclear bomb? Einstein said the world had changed since the discovery of the splitting of the atom...

It's true. The world has changed.

Oppenheimer knew it would.

Oppenheimer is dead. He's done something for the world, and people don't understand it. The world is free thanks to him.

One last question: when you hear everyone say that a nuclear bomb should be dropped on these people, how do you react?

Oh, if I had the power, I wouldn't hesitate for a second. I would wipe them off the map. It would cost innocent lives, but we have never fought a war anywhere in the world without our enemies attacking innocent people too. If only the newspapers could cover these kinds of events other than by reporting on the too many civilians we sacrifice. These people are just in the wrong place at the wrong time.

By the way, I forgot to say that Enola Gay was initially called number 82. How did your mother react when she saw her name written on it?

Well, I can only tell you what my father told me about it. My mother was not one to let her emotions show, whether it was something serious or something light, but when she was made to laugh, her stomach would start to jiggle. My father told me that when the phone rang at their house in Miami, my mother was very calm at first. And then, when the news was announced on the radio, her stomach started doing one of these jigs.

Interview published on August 6, 2002 in The Guardian and translated from English by the magazine More than words n°11, summer 2014.

Related Articles