By akademiotoelektronik, 27/03/2023

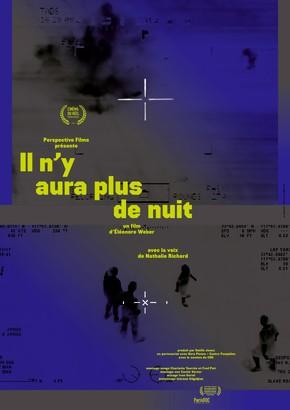

Film of the week: “There will be no more night” by Eléonore Weber Twitter feed

Can we conceive of a 'clean' war where we do not see the face of the enemy nor his blood flow nor his flesh tear? In any case, this is what soldiers and followers of new technologies of targeted destruction mean to us, from thermal cameras to remotely controlled drones. To address this question (and many others), Eléonore Weber, scenographer and filmmaker, decides to take a closer look at the images (free access on the net), recorded by French or American pilots of combat helicopters equipped with infrared sights. Before our eyes, they film, aim and shoot. However, this gripping documentary does not only question the way of bringing death to men transformed into luminous silhouettes in a landscape cut out clearly in black and white. At the edge of video games and science fiction, "There will be no more night" turns into a political fable. The archive images, here finely arranged and distanced by a visionary commentary, question the gaze (which kills) of soldiers on special missions, our gaze – between fascination and fear – in the face of this strange spectacle. As if the obsession with all technological power, by dint of seeing, monitoring and punishing, prefigured, beyond warlike aims, the 'democratic' lure of societies without night or mystery.

In the eye of the shooter

Aerial views with colors and landscapes that are difficult to recognize. We are flying over, at night, sometimes tens of kilometers above war zones in Afghanistan, Iraq or Pakistan, but we don't know it. For the moment, we are on board a military helicopter, we hear the characteristic noise produced by the whirling of the blades, instead of the pilot since the images are the (subjective) product of his exclusive point of view. The movements of his head determine the changes in the angle of view and the infrared thermal camera is at the same time a sight that can trigger a machine gun shot intended to eliminate the supposed enemies spotted in the form of silhouettes made luminous by the heat of the bodies. Hence the pattern of the viewfinder appeared superimposed and present almost during all the sequences.

‘These images are not made to be watched’ tells us the beautiful, detached and deep voice of actress Nathalie Richard in the voice-over commentary. However, such images, classified as 'secret defence', posted most of the time by French or American veterans, are accessible on general public sites (Dailymotion, YouTube, etc.) or military sites (military.com). And the discovery of this material, both unusual and terrifying, is the engine of Eléonore Weber's intellectual and artistic approach.

Death Live: Crossed Views

It is, indeed, for the filmmaker to question the status of these archives where the camera is intrinsically associated with a “war project”. The man with the camera sees from above and from afar (even if he can zoom in at breakneck speed right on his target to the point of distinguishing the texture of the garment without discerning the face). After a brief exchange (or consultation) with the co-pilot, the designated shooter makes the decision to kill (or not). On the ground, in wooded landscapes, arid mountains or, sometimes, in the heart of cities, transformed by the infrared camera into unreal territories, in fluorescent black and white, luminous figurines move in the night, slowly or at full speed. according to the supposed degree of danger (or in the indifference of civilian populations accustomed to numerous overflights of helicopters not always bringing death).

Before our eyes, tearing the silence of the cockpit and that of the region overflown (from which no sound reaches us), the submachine gun spits fire. Below, the figures attempt to evade fire, hide weapons in the sparse bushes, and crumble one by one until the business of death and the mission to check the outcome are recorded as complete. And kept by the military on a USB key.

And we spectators, in a growing uneasiness, cannot take our eyes off this vision: faceless men transformed into wandering ghosts who have barely had time to see death coming. The dead disappeared in a cloud of white dust or the deep crater of an explosion, without a cry heard or a trace of blood visible.

Beauty and horror

No complacency or pathos, however, in the deciphering enterprise proposed by the director. An important testimony, that of a French pilot, under the pseudonym of Pierre V., prompted by the initiator of this ambitious project, deepens the reflection to the point of redirecting the commentary initially written by Eléonore Weber. The pilot in question, far from questioning the validity of his mission, recognizes a disturbance caused by the technologies of viewing and the aesthetics, even the beauty, produced by the transformation of the perception of the world that they induce. We ourselves as spectators experience it, from the back of the cinema, the disturbing experience.

The territories, thus captured by the infrared cameras, navigate on the edges of the fantastic, struck by an intense brilliance, in particular with the amplification of the twinkling of the stars. Sometimes lunar lands on the surface of which ghosts move without us being able to really recognize the country or the region concerned; an off-screen voluntarily maintained by Eléonore Weber in order to confront us with what concerns us all, beyond the geopolitical context and the power of fascination, of 'this strange beauty which casts a veil over horror', according to the observation of the latter.

And the dread seizes us again over the course of lightning sequences. The power of seeing machines leads to terrible paradoxes: the more warrior pilots see and push the limits, the less sure they are of what they see. A peasant carrying a rake can be mistaken for a fighter with a Kalashnikov. A photographer carrying his camera in the middle of the street can be mistaken for an armed terrorist. Apart from rare blunders brought to light, these soldiers, bearers of a warlike technology in search of an operational vision and limitless efficiency, appear to us as the pure products of our Western societies, haunted by the omnipotence of the visible. .

Underground praise of mystery

In “There will be no more night”, -it is the very principle of the film-, no reverse shot is possible to the images recorded from the point of view of the pilot and shooter. We will therefore never see how the people under scrutiny live below. We will never see each other's faces. Only once, at the end of the trip, during the return of an American serviceman to the house, some awkward images show us his young children showing by leaping and smiling the joy of seeing their father again. Like the traditional representation in cinema of the return of the solitary 'cowboy' among his own, his fellows. At the antipodes of a strange sequence where pilots, abandoning their sights, suspend their killer mission for a short time, to film children playing from afar as they fly over this foreign land. Like the breaking and entering of a fragment of humanity that they will have to drive out of their memory to continue.

In other words: Eléonore Weber's stunning documentary does not intend to let us sleep in peace. Faced with the all-powerful dream of our societies haunted by transparency and the all-out surveillance of people and places, made possible by increasingly sophisticated remote viewing technologies, "There will be no more night" pleads with intelligence in favor of chiaroscuro, shadow areas. Of the irreducible mystery that founds our humanity.

Samra Bonvoisin

"There will be no more night", film by Eléonore Weber-release June 16, 2021.

Related Articles