By akademiotoelektronik, 06/04/2022

Air & Cosmos 50 years ago, Apollo 10, the mission that grazed the Moon Air & Cosmos

After the successful Apollo 9 mission which tested lunar hardware from Earth orbit, Apollo 10 was to test from lunar orbit the entire lunar train – consisting of a Command and Service Module (CSM) and a lunar module (LM). All the operations necessary for a human landing were going to be implemented with the exception of the moon landing.

A capital mission...criticized.

The Apollo 10 mission was criticized both in the general public and within NASA. If the LM is called upon to perform a maneuver to get closer to the lunar ground, why shouldn't the crew attempt the moon landing? For those in charge of the mission, this was considered "premature and reckless", in the words of General Samuel C. Philips, the director of the Apollo program from 1964 to 1966. Indeed, there were still uncertainties: until then, only a CSM (Apollo 8) had approached the Moon, but without LM; as for the lunar train, it had only been tested once, but from Earth orbit (Apollo 9). Before landing, a crucial question therefore remained to be resolved: how would the lunar train in general and the LM in particular behave in the gravitational field of the Moon at very low altitude?

A mission followed live.

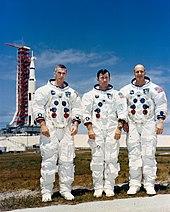

On May 18, the Saturn 5 launcher successfully launches Apollo 10. On board is the most experienced crew ever assembled: Commander Thomas P. Stafford (who flew in Gemini 6 and 9), CSM pilot John W. Young (Gemini 3 and Gemini 10), and LM Pilot Eugene A. Cernan (Gemini 9). A few hours later, the CSM separates from Saturn IVB, the last stage of Saturn 5, and proceeds to dock with the LM to form the lunar train. For the first time, the operation is broadcast in color on television.

During the trip to the Moon, the astronauts repeatedly carry out television broadcasts to the delight of viewers…and American propaganda. After presenting the emblem of the Apollo 10 mission to the camera, John Young also shows viewers drawings of Charlie Brown and Snoopy, famous characters and dogs created in 1950 by Charles M. Schulz. The crew had selected the first to baptize the CSM, the second for the LM. Note that the dog Snoopy was already used within NASA as an emblematic figure of the space adventure. Astronauts also show what life in microgravity consists of, in particular with objects that “fly”. Finally, on several occasions, they point their camera in the direction of the Earth and, at 80,000 km, Cernan lets go: “The Earth is in the middle of nothingness. It's hard to believe."

Snoopy thinks he's a top.

The CSM-LM train arrives on May 21 in the lunar suburbs and is placed in orbit. On May 22, after Stafford and Cernan joined the LM, it separated from the CSM in which John Young lived (becoming the first man to fly solo around the Moon). One of the most important parts of the mission begins, and with great uncertainty, as Cernan recalled: "None of us knew at the time what might happen next, and if Snoopy and Charlie Brown had a chance to meet again one day. There were no guarantees”.

Little by little, Snoopy moves away from Charlie Brown. The descent is filmed and photographed. When Snoopy approaches the lunar ground, Cernan experiences a particular sensation: “We had the impression of flying over the Arizona desert. But no desert was like this place.” And Stafford: “It's a fabulous sight. There are different shades of brown and gray.”

About 15 km from the lunar surface, Cernan triggers the separation of the two stages of the LM, so that the ascent stage can join the CSM. Suddenly, Snoopy bows, then starts spinning. The two astronauts cut off the autopilot and thus restore the balance of the small vessel. However, the ignition does not work… Cernan swears. Fortunately, the auxiliary system takes over, finally allowing the ascent to Charlie Brown. In total, Snoopy's getaway lasted eight and a half hours, including eight minutes for the incident. The latter thus put the LM to the test, but also the crew, which reacted with composure, thanks to prior training through numerous tests and simulators… and the permanent support of the mission controllers on Earth. .

The return.

On May 24, at the 31st revolution, the time comes to relight the engine of the CSM to leave lunar orbit and return to Earth. Anguish rises within the crew… The engine is reignited and runs perfectly. Phew. Shortly before leaving lunar orbit, Stafford declares: "I believe that we will have much to do around here in the years to come, if we want not only to look, but also to explore these pleasant regions".

The return flight went off without a hitch; the astronauts take the opportunity to make new TV shows and even a live shaving session (the first in history). In total, 19 television broadcasts will have been made! Another record was also obtained: during the return, the Apollo spacecraft reached the impressive speed of 39,896 km/h. On May 26, the CSM capsule successfully landed near the Samoa Islands, in Polynesia.

Report and media coverage.

If the Apollo 10 mission did not land on the moon, it nevertheless had an important role in achieving all the expected objectives, including mastering navigation in lunar orbit, evaluating the performance of the lunar train, the test of the behavior of the LM in the descent and ascent phase, the location of the landing site for the next mission. Apollo 10 was therefore not just a simple dress rehearsal.

Finally, Apollo 10 obtained a considerable echo in the American and foreign media. Thus, on June 6, the American weekly Life publishes in “one” extraordinary photos of the mission under the title “Barnstorming the Moon” (triumphant tour around the Moon); on June 9, the same weekly published a special issue with the title "The Great Adventure of Apollo 10".

Similarly, in France, the media are captivated by the prowess of Apollo 10: La Montagne of May 20 headlines: “Apollo 10. Perfect flight”; on the same day, The New Republic : “Race without history of Apollo 10”, etc. The return is greeted as it should be: on May 27, La Nouvelle République publishes on the front page: “The triumph of the Americans after the 110% success of the Apollo 10 mission”; Le Parisien liberated title in red: “A star descended from the sky… it was Apollo 10 which returned from the Moon”, with in black ink superimposed “PRODIGIOUS! ". Many color photographs are published in particular in Le Patriote illustré of June 8, 1969, in Paris Match of June 14, 1969, etc. In the latter, the great chronicler Raymond Cartier writes: “In a month, God permitting, the most prodigious adventure in history will begin. Here is this Moon that man is going to conquer…”.

References

The Apollo 10 Flight Journal, The Apollo 10 Flight Journal, David Woods, Robin Wheeler, Ian Roberts

A book: Conquest of the Moon, Dr Herbert Pichler, Buchet/Chastel, Paris, 1969

A testimony: Eugene Cernan and Don Davis, I was the last man on the Moon, Altipresse, 2010

A video about the Apollo 10 launch and mission.

Philippe Varnoteaux is a doctor in history, a specialist in the beginnings of space exploration in France and the author of several reference works.

Soon the fiftieth anniversary of Apollo 11...

For the occasion, a special issue of Air & Cosmos will appear. More than 100 richly illustrated pages that will take you back to the journal's archives and (re)discover behind the scenes of the feat thanks to the articles of 15 specialists, all commented on by 35 personalities.

From June 14 on newsstands and at the Paris Air Show. €12.90.

Related Articles